Show Transcript:

The Big Idea

Make sure your time investments have an ROI.

Questions I Answer

- How can I feel confident in my decision making?

- What is sunk cost bias?

- How does sunk cost bias affect my decisions?

- Is there a strategy I can use to help me make better decisions?

Actions to Take

- Take a hard look at the things you do in your life that don’t make you happy. Are you just doing them because of sunk cost bias?

Key Topics in the Show

-

How sunk cost bias influences bad decisions.

-

How fear of failing and being wasteful makes you lose sight of your goals.

-

The easy mindset shift to reverse sunk cost bias.

-

An accounting technique that will help you justify and allocate your time.

Resources and Links

- Tips on How to Make Better Decisions Using Sunk Cost Bias:

- Pretend you don’t own the item, opportunity or project yet and change the way you question yourself.

- Item: “How much do I value this item?” vs. “If I did not own this item, how much would I pay to obtain it?”

- Opportunity: “How will I feel if I miss out of this opportunity?” vs. “If I wasn’t already involved in this opportunity how hard would I work to get on it?”Would you work as hard as you currently are on it or would you say “This is not worth my time”?

- Project: “Why stop now when I’ve already invested so much in this project?” vs. “If I wasn’t already invested in this project, how much would I invest in it now?”It’s not “If I just keep trying I can make this work,” it’s really about “What else could I do with this time, money, or energy if I pull the plug right now?”

- Pretend you don’t own the item, opportunity or project yet and change the way you question yourself.

Hello, hello everyone. Welcome to Productivity Paradox. I’m your host, Tanya Dalton, and this is episode 16. Today, we are going to be talking about making decisions and avoiding sunk cost bias.

I think decision-making is really important to when we’re talking about productivity because everything we do requires a choice making a decision, but for a lot of people, decisions can be really difficult to make. We get really caught up in making the perfect decision, knowing exactly what we should be choosing, and there are no perfect decisions. Most of decision-making is educated guesses.

We also fear making the wrong call. We talked a lot about this last week in episode 15, when we talked about the fear of missing out and not saying yes to every opportunity. If you find that you experience a lot of FOMO or fear of missing out, I do suggest you go back and give a quick listen to episode 15 just to get an idea of how you can look at that a little bit differently.

Today, what I really want to focus in on is the biggest issue, I think, most people have with making decisions, and that is sunk cost bias or sunk cost fallacy. They’re the same thing. Just two different words to describe them. I feel like the best way to avoid sunk cost bias is to learn about it because this is something almost every single person deals with.

Sunk cost bias is essentially the tendency to continue to invest time, money or energy into something we know is a losing proposition just because we’ve already incurred or sunk cost that cannot be recouped. Again, that cost could be time. It could be money or it could be energy.

What happens is this causes a vicious cycle because the more we invest, the more determined we become to see it through because we want to see our investment pay off, so we get a little stubborn and we get in this cycle where we keep pouring more time or more energy or more money into something, even though we know it’s not really going anywhere. The more we invest, the harder it is to let go.

This really explains why we continue to, I don’t know, slog through a terrible movie because we already paid for a ticket. We’ve all done that, where you pay for a ticket to go to a movie and about 20 minutes in, you realize this is awful, but we don’t get up and leave the theater. Most of us will go ahead and sit for the next two hours, sometimes, three, through a terrible movie simply because we purchased the ticket.

This also explains why we continue to put money into these home renovations that never seem to go near completion or why we invest so much time and energy into toxic relationships even when we know that our efforts are not making things better. You know what I’m talking about. That person you dated for way too long, knowing it wasn’t going anywhere, but you still stayed through.

©Productivity Paradox Page 1 of 6

That’s sunk cost bias, and it contributes to you making bad decisions because it’s so hard to walk away when we’ve invested so much in these things even if it is just a $10 movie ticket. It becomes so much more difficult. Why is this?

I want to talk to you in terms of our tasks because obviously, we’re really focusing in on productivity, but I think discussing it in terms of belongings will really help to explain what I mean because there is a phenomenon known as the endowment effect. The endowment effect is a tendency to undervalue the things that are not ours and to overvalue the things because we already own them.

Nobel prize winning researcher, Daniel Kahneman, did a study researching the endowment effect. What he did was he randomly gave coffee mugs to half of the subjects in this experiment. The people with the coffee mugs, he asked how much they would be willing to sell their mug for, then he asked the other half, the people without the mugs, how much they would be willing to spend to buy the mugs.

Here’s what’s interesting. The subjects who own the mugs would sell them for no less than $5.25, but the people without the mugs were only willing to pay $2.75 at the very most. The mere fact of ownership cause those mug owners to value the objects more highly, and it made them less willing to part with them, even though they were the exact same mugs.

When you think of items in your life that are more valuable, the moment you start thinking about giving them away, you can think about the book sitting on your bookshelf that you’ve promised yourself you’re going to read, but you haven’t done it. Maybe the kitchen appliance that’s sitting in a box or that hideous sweater your aunt gave you for the holidays two years ago and you’ve never worn.

Even though you’re not getting any use or enjoyment out of these objects, subconsciously, the very fact that they are yours, that you own them, somehow makes them more valuable than if they didn’t belong to you. Does that make sense?

Now when you think of it that way, let’s think about this in terms of projects. Whenever you’re in a project that doesn’t feel like it’s going anywhere, it somehow feels more critical when you’re the team leader or the commitment to volunteer at, I don’t know, the local bake sale becomes harder to get out of when you’re the one in charge of the larger fundraiser altogether. When we feel that we own an activity, it becomes really hard to uncommit, and this is the endowment effect.

Why are we so susceptible to this cost bias and how can we stop giving in to it? I think a lot of it, honestly, boils down to that lifetime of exposure we all get to the “Don’t waste” rule. We’re trained to avoid appearing wasteful, and abandoning an item or a project that you have invested a lot into feels like you’ve wasted everything, and we are told to avoid waste.

You can really clearly see this with people who were raised during the Depression era. My grandpa was raised in the Depression era. He was a wonderful man who was raised in the Midwest, and he was so smart. He could’ve been a brilliant inventor, but he could not help but give in to sunk cost bias because of the way he

©Productivity Paradox Page 2 of 6

was raised and the Depression era he lived through. He was taught never to waste, so, of course, he had sunk cost bias.

Even with things like slivers of soap, so much the amusement of us, his family, my grandpa would gather together those tiny little slivers of soap in the showers. You know, when you’re taking a shower with a bar of soap and the soap gets so small, you really can’t use it any longer. My grandpa saw that as an investment in the soap, so he would gather those together and he would take them and put them in my grandma’s blender, which did not make my grandma happy, and add a little water and blend it up to make liquid soap.

As you can imagine, this liquid soap was awful to use because there were these giant chunks of soap that would come out and to be honest with you, nobody liked using it. I secretly think even he didn’t like using it, although he never would’ve admitted that, but he really didn’t want anything to go to waste even soap. He wanted that investment that he spent even if it was $1.20. He wanted it to feel like it was worthwhile.

That’s really what it boils down to. We all want to make our investments feel worthwhile. We don’t want to feel like we’ve spent anything in vain, whether it’s time or money or energy. Even when we know deep down inside our approach is wrong, we really have a hard time abandoning it.

We want a good return on our investments, so you just have to make sure you’re not in a situation solely because you made the investment in the first place. You don’t make a bad move better by spending more time and energy on it unless you can truly change that expected outcome. It’s okay to cut your losses and move on. Not every investment is going to be worthwhile.

We also fear failing and looking foolish. Every single one of us fears looking foolish. Our egos don’t want us to admit imperfection even to ourselves. Allow yourself to make mistakes though and admit them. If you’ve been listening to this podcast for any length of time, you know that I talk a lot about learning from our mistakes because I truly believe that is the best way for us to learn.

It’s much more productive to cut your losses than to keep entrenching yourself in situations just to save face. Become proud of admitting your errors. I love that saying, “Show your scars, not your wounds,” because when we have a cut on ourselves, it’s really hard to show. We need that time for these failures or these mistakes to heal a little bit, so we can look at them with the eyes of reflection. I think that’s really important.

You have to become proud of admitting your errors, and that’s a difficult thing to do because we all have a little bit of ego in ourselves that we don’t want to look foolish. I feel that way just as much as you do, but instead of focusing on the sunk cost, it’s good to take some pride in recognizing the cost that you’re actually going to incur with sticking with that old approach and being okay with rerouting.

Here is, again, where I think flexibility is the key when you’re doing any sort of planning or projecting because one of the things that happens is we tend to lose

©Productivity Paradox Page 3 of 6

sight of our goals. When we’re really entrenched in the sunk cost bias, we end up putting so much effort into something. We lose sight of its relevance in the grand scheme of our goals. By keeping your goals visible, you can clearly see what tasks really fit and what the sunk cost bias things really are.

We become really attached to our commitments and the bigger the commitment, the harder it is to let go even if that perceived commitment is a big commitment in your own mind. Here’s a good example of that. Painting a room. A lot of people see that as a big commitment, even though when you paint a room, you can easily paint over it.

Here’s a good example that shows how using sunk cost can help you spend your time and your energy and your money a little wiser. I’ve seen this example somewhere. I can’t remember where, but I thought it was really, really good.

Imagine you are painting a room. You go and you buy a gallon of paint, and you spend $25 on that gallon of paint to paint your bedroom. You start rolling it on the walls and immediately, you hate it. It’s not at all what you envisioned. The color is all wrong, but you know what, you’ve already bought that gallon of paint, so you go ahead and you start painting the room and about halfway through, you ran out of paint. Right there, what are you going to do?

Most people will go buy another gallon of that same paint, thinking to themselves, “Well, I’ve already spent the time. I’ve already spent 25 bucks. I’m going to go ahead and paint the rest of the room and just be done with it.” You go back to the store and you buy another $25 gallon of paint.

At this point, you’ve spent $50 painting this room, and you live in this room for, let’s say, three months, and the whole time, you hate it. The color is all wrong. You’re not happy, so eventually, you’re going to decide to repaint that whole room, so that next time you’re going to go to the paint store and you have to get your two gallons of paint, so that there you spent $50 again.

You spent $25 on the first ugly gallon of paint, $25 on the second gallon of ugly paint, and then $50 fixing all that painting, so you spent a total of $100, but if you would’ve stopped after that first gallon ran out and you said, “You know what, I’m just going to start again. I’m going to get a color I really like,” you would’ve spent $75.

Right there, you can see, you would save $25 in this scenario, but it’s not just the money. It’s also the time and the energy you spent painting the same room twice because of sunk cost. I feel like that’s a really powerful example because you get really caught up when it seems like a big commitment, but with the paint, all you have to do is paint over it.

The question really is, can we avoid sunk cost bias? Can we start making better decisions for ourselves? I think the answer is easy. It’s yes. All we have to do is pretend you don’t own it yet.

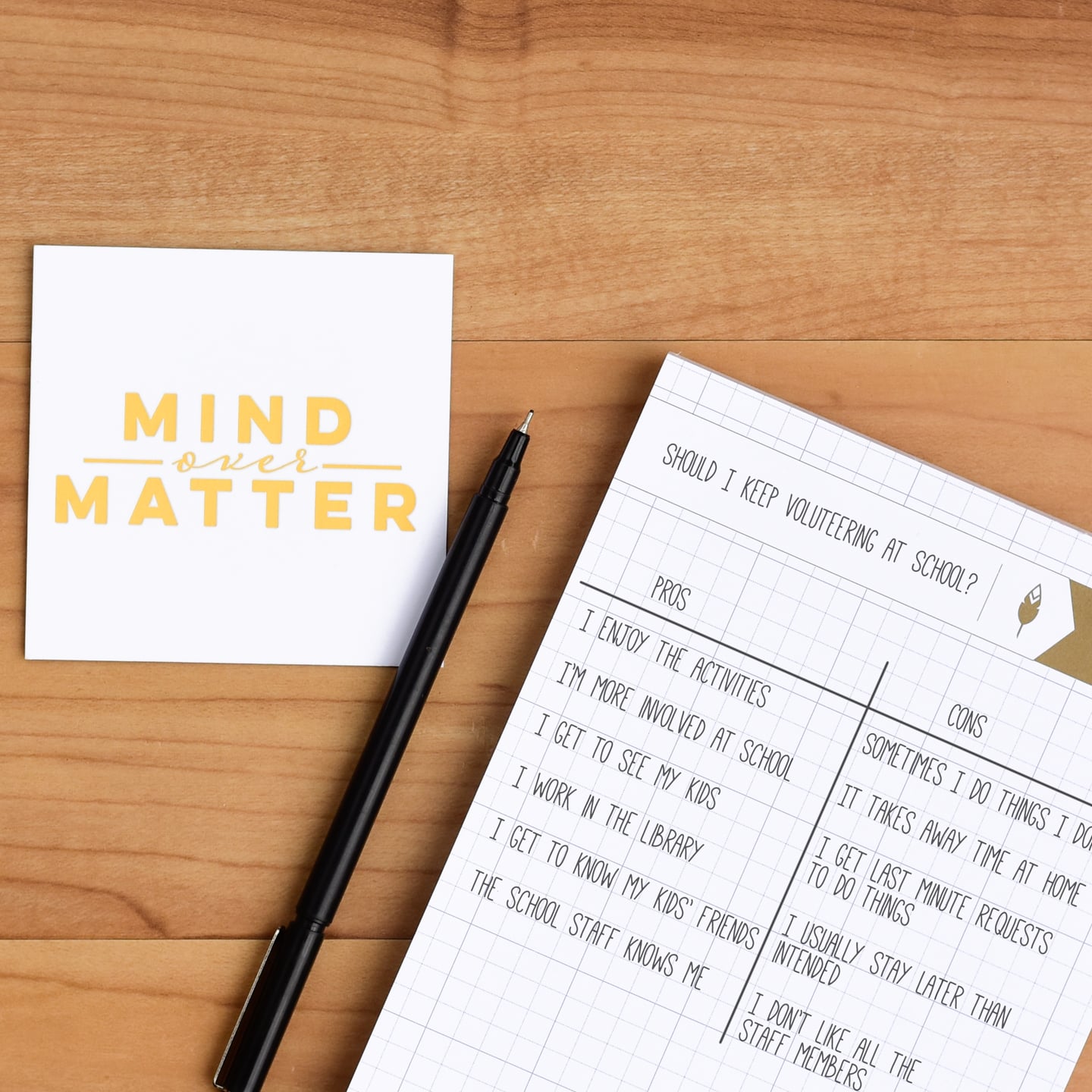

Start by changing the way you question yourself. We all question ourselves when we’re struggling with the decision on anything. We do pro-con-pro list. We

©Productivity Paradox Page 4 of 6

write out what would be good, what would be bad, but it’s really all about changing the way you think. Make sure you’re asking yourself the right question.

Let met tell you what I mean. Let’s say, it’s an object that you’re making a decision on. Instead of asking, “How much do I value this item,” ask yourself, “If I did not own this item, how much would I pay to obtain it?” You can see that the question is slightly different because I don’t want to know how much you think that item is worth. I want to know how much you would pay to obtain it if you didn’t own it.

For an opportunity, instead of asking, “How will I feel if I miss out on this opportunity,” try asking yourself, “If I wasn’t already involved in this opportunity, how hard would I work to get on it?” Would you work as hard as you’re working right now to get on that opportunity or would you say, “This is not worth my time”? Again, pretend that you’re not already involved.

For a project, instead of asking, “Why stop now, when I’ve already invested so much in this project,” try asking yourself, “If I wasn’t already invested in this project, how much would I invest in it now?”

It really is about taking your questions and turning them a little bit on their head, so that you’re looking at it from an outsider’s point of view of what is the value. It’s not “If I just keep trying, I can make this work.” It’s really about “What else can I do with this time or this money or this energy if I pulled the plug right now?”

Now what I’ll do is I’ll list those questions out in my show notes, which you can always access my show notes at inkwellpress.com/podcast and look under episode 16, if you want to look at those and start questioning some things using this questioning method.

Another thing that you can do to help avoid sunk cost bias is borrowing a principle from accounting and apply zero-based budgeting. Zero-based budgeting is typically where accountants start with a zero. Now what most accountants do is they allocate a budget based on last year’s budget, and they use that as a baseline for the following year’s projections.

With zero-based budgeting, you start from zero. Everything on the budget must be justified from scratch. This type of accounting takes a lot more effort, but it efficiently allocates resources on the basis of need rather than history, and history is what causes that sunk cost bias.

Why do they do it this way? Well, it helps to find exaggerated budget requests, and it draws attention to obsolete operations and it encourages people to be clear with their purpose and how those expenses align with their projects.

We’re always talking about your time in terms of being revenue, right? It’s a fluid resource just like our money is, so think about your time as a budget and budget it with zero-based accounting in mind. Assume all previous commitments are gone and you are starting from scratch. Every use of your time, your energy, and your resources have to justify themselves from zero, whether it’s work or relationships or

©Productivity Paradox Page 5 of 6

projects or hobbies, and use this lens to make your decisions without the bias of sunk cost being involved.

I hope that all makes sense. It’s really about looking at things from an outsider’s point of view and justifying things as if they do not already belong to you. My biggest walkaway I want you to have with this episode is that I want you to have the courage and the confidence to admit your mistakes and to feel that it’s okay to uncommit no matter what the sunk costs have been.

It doesn’t matter if you have sunk three years into a relationship with someone. If it is toxic, it’s okay to cut those ties and walk away or if it’s a project that you feel has just sucked away all of your time and maybe even some of your happiness, it’s okay to look at that and say, “I’ve got to move on from it.” It’s all right to not feel like you have to keep moving forward with it.

Next week, we’re going to be talking about the lost art of quitting, and thinking through your sunk cost bias will really help us in moving forward and figuring out what are the things that we really want to quit.

I feel like quitting has a really bad connotation. People think, “It’s terrible to quit things.” We’re going to kind of put that on its head and talk about why quitting is an art form and why it really fits in with our decision-making.

What I want to encourage you to do is during this week, between this episode and next episode coming out, I want you to really think about your sunk cost bias, and I want you to take a good, hard look at the things that are going on in your life that don’t necessarily make you happy. Are you sticking with these things because of the sunk cost bias or are you sticking with them because they really are going to make you happy? Really looking at it from that outsider point of view.

Again, I’ll have those questions listed for you in the show notes at inkwellpress.com/podcast, because I really think that’s a great way to look at things when you are making your decisions, because I really want you to feel confident when making your decisions, but keep in mind, there are no perfect decisions out there. Decisions are really that. They’re decisions that are made from your heart and your head working together.

I’d love for you to connect with me. You can find me on social media, on Instagram and Facebook, especially, using the username, inkwellpress. You can email me at hello@inkwellpress.com or you can find me at inkwellpress.com.

Again, the show notes for this episode are under inkwellpress.com/podcast, episode 16. I’m really excited about how this season is turning out, and I’m excited for us to be streamlining together. Until next time, happy planning.

**This transcript is created by AI, so please excuse any typos, misspellings and grammar mistakes.

Tanya Dalton is a top woman productivity expert and speaker. Her talks are both inspiring and motivating, causing her audience to claim that she is the best female keynote speaker.